According to a top religion scholar, this 1,600-year-old text fragment suggests that some early Christians believed Jesus was married -— possibly to Mary Magdalene

by Ariel Sabar

Smithsonian.com

September 18, 2012

Harvard researcher Karen King today unveiled an ancient papyrus fragment with the phrase, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife.’” The text also mentions “Mary,” arguably a reference to Mary Magdalene. The announcement at an academic conference in Rome is sure to send shock waves through the Christian world. The Smithsonian Channel will premiere a special documentary about the discovery on September 30 at 8 p.m. ET. And Smithsonian magazine reporter Ariel Sabar has been covering the story behind the scenes for weeks, tracing King’s steps from when a suspicious e-mail hit her in-box to the nerve-racking moment when she thought the entire presentation would fall apart. Read our exclusive coverage below.

Harvard Divinity School’s Andover Hall overlooks a quiet street some 15 minutes by foot from the bustle of Harvard Square. A Gothic tower of gray stone rises from its center, its parapet engraved with the icons of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. I had come to the school, in early September, to see Karen L. King, the Hollis professor of divinity, the oldest endowed chair in the United States and one of the most prestigious perches in religious studies. In two weeks, King was set to announce a discovery apt to send jolts through the world of biblical scholarship—and beyond.

King had given me an office number on the fifth floor, but the elevator had no “5” button. When I asked a janitor for directions, he looked at me sideways and said the building had no such floor. I found it eventually, by scaling a narrow flight of stairs that appeared to lead to the roof but opened instead on a garret-like room in the highest reaches of the tower.

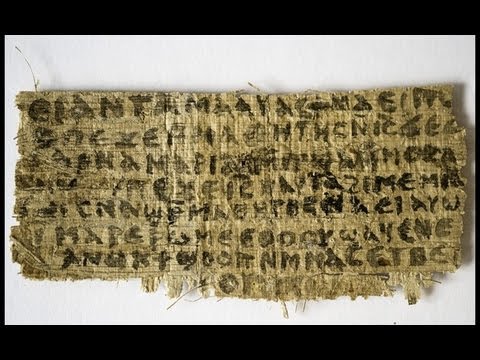

“So here it is,” King said. On her desk, next to an open can of Diet Dr Pepper promoting the movie The Avengers, was a scrap of papyrus pressed between two plates of plexiglass.

The fragment was a shade smaller than an ATM card, honey-hued and densely inked on both sides with faded black script. The writing, King told me, was in the ancient Egyptian language of Coptic, into which many early Christian texts were translated in the third and fourth centuries, when Alexandria vied with Rome as an incubator of Christian thought.

When she lifted the papyrus to her office’s arched window, sunlight seeped through in places where the reeds had worn thin. “It’s in pretty good shape,” she said. “I’m not going to look this good after 1,600 years.”

But neither the language nor the papyrus’ apparent age was particularly remarkable. What had captivated King when a private collector first e-mailed her images of the papyrus was a phrase at its center in which Jesus says “my wife.”

The fragment’s 33 words, scattered across 14 incomplete lines, leave a good deal to interpretation. But in King’s analysis, and as she argues in a forthcoming article in the Harvard Theological Review, the “wife” Jesus refers to is probably Mary Magdalene, and Jesus appears to be defending her against someone, perhaps one of the male disciples.

“She will be able to be my disciple,” Jesus replies. Then, two lines later, he says: “I dwell with her.”

The papyrus was a stunner: the first and only known text from antiquity to depict a married Jesus.

But Dan Brown fans, be warned: King makes no claim for its usefulness as biography. The text was probably composed in Greek a century or so after Jesus’ crucifixion, then copied into Coptic some two centuries later. As evidence that the real-life Jesus was married, the fragment is scarcely more dispositive than Brown’s controversial 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code.

What it does seem to reveal is more subtle and complex: that some group of early Christians drew spiritual strength from portraying the man whose teachings they followed as having a wife. And not just any wife, but possibly Mary Magdalene, the most-mentioned woman in the New Testament besides Jesus’ mother.

The question the discovery raises, King told me, is, “Why is it that only the literature that said he was celibate survived? And all of the texts that showed he had an intimate relationship with Magdalene or is married didn’t survive? Is that 100 percent happenstance? Or is it because of the fact that celibacy becomes the ideal for Christianity?”

How this small fragment figures into longstanding Christian debates about marriage and sexuality is likely to be a subject of intense debate. Because chemical tests of its ink have not yet been run, the papyrus is also apt to be challenged on the basis of authenticity; King herself emphasizes that her theories about the text’s significance are based on the assumption that the fragment is genuine, a question that has by no means been definitively settled. That her article’s publication will be seen at least in part as a provocation is clear from the title King has given the text: “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.”

* * *

King, who is 58, wears rimless oval glasses and is partial to loose-fitting clothes in solid colors. Her gray-streaked hair is held in place with bobby pins. Nothing about her looks or manner is flashy.

“I’m a fundamentally shy person,” she told me over dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in early September.

King moved to Harvard from Occidental College in 1997 and found herself on a fast track. In 2009, Harvard named her the Hollis professor of divinity, a 288-year-old post that had never before been held by a woman.

Her scholarship has been a kind of sustained critique of what she calls the “master story” of Christianity: a narrative that casts the canonical texts of the New Testament as divine revelation that passed through Jesus in “an unbroken chain” to the apostles and their successors—church fathers, ministers, priests and bishops who carried these truths into the present day.

According to this “myth of origins,” as she has called it, followers of Jesus who accepted the New Testament—chiefly the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, written roughly between A.D. 65 and A.D. 95, or at least 35 years after Jesus’ death—were true Christians. Followers of Jesus inspired by noncanonical gospels were heretics hornswoggled by the devil.

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/The-Inside-Story-of-the-Controversial-New-Text-About-Jesus-170177076.html#ixzz279Advh2M

Add comment